Polyester is a category of polymers that contain one or two ester linkages in every repeat unit of their main chain.[1] As a specific material, it most commonly refers to a type called polyethylene terephthalate (PET). Polyesters include some naturally occurring chemicals, such as those found in plants and insects. Natural polyesters and a few synthetic ones are biodegradable, but most synthetic polyesters are not. Synthetic polyesters are used extensively in clothing.

Polyester fibers are sometimes spun together with natural fibers to produce a cloth with blended properties. Cotton-polyester blends can be strong, wrinkle- and tear-resistant, and reduce shrinking. Synthetic fibers using polyester have high water, wind, and environmental resistance compared to plant-derived fibers. They are less fire-resistant and can melt when ignited.[2]

Liquid crystalline polyesters are among the first industrially used liquid crystal polymers. They are used for their mechanical properties and heat-resistance. These traits are also important in their application as an abradable seal in jet engines.[3]

Types

[edit]

Polyesters can contain one ester linkage per repeat unit of the polymer, as in polyhydroxyalkanoates like polylactic acid, or they may have two ester linkages per repeat unit, as in polyethylene terephthalate (PET).

Polyesters are one of the most economically important classes of polymers, driven especially by PET, which is counted among the commodity plastics; in 2019 around 30.5 million metric tons were produced worldwide.[4] There is a great variety of structures and properties in the polyester family, based on the varying nature of the R group (see first figure with blue ester group).[1]

Natural

[edit]

Polyesters occurring in nature include the cutin component of plant cuticles, which consists of omega hydroxy acids and their derivatives, interlinked via ester bonds, forming polyester polymers of indeterminate size. Polyesters are also produced by bees in the genus Colletes, which secrete a cellophane-like polyester lining for their underground brood cells[5] earning them the nickname “polyester bees”.[6]

Synthetic

[edit]

The family of synthetic polyesters comprises[1]

- Linear aliphatic high molecular weight polyesters (Mn >10,000) are low-melting (m. p. 40 – 80 °C) semicrystalline polymers and exhibit relatively poor mechanical properties. Their inherent degradability, resulting from their hydrolytic instability, makes them suitable for applications where a possible environmental impact is a concern, e.g. packaging, disposable items or agricultural mulch films[7] or in biomedical and pharmaceutical applications.[8]

- Aliphatic linear low-molar-mass (Mn < 10,000) hydroxy-terminated polyesters are used as macromonomers for the production of polyurethanes.

- hyperbranched polyesters are used as rheology modifiers in thermoplastics or as crosslinkers in coatings[9] due to their particularly low viscosity, good solubility and high functionality[10]

- Aliphatic–aromatic polyesters, including poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) and poly(butylene terephthalate) (PBT), poly(hexamethylene terephthalate)(PHT), poly(propylene terephthalate) (PTT, Sorona), etc. are high-melting semicrystalline materials (m. p. 160–280 °C) that and have benefited from engineering thermoplastics, fibers and films.

- Wholly aromatic linear copolyesters present superior mechanical properties and heat resistance and are used in a number of high-performance applications.

- Unsaturated polyesters are produced from multifunctional alcohols and unsaturated dibasic acids and are cross-linked thereafter; they are used as matrices in composite materials. Alkyd resins are made from polyfunctional alcohols and fatty acids and are used widely in the coating and composite industries as they can be cross-linked in the presence of oxygen. Also rubber-like polyesters exist, called thermoplastic polyester elastomers (ester TPEs). Unsaturated polyesters (UPR) are thermosetting resins. They are used in the liquid state as casting materials, in sheet molding compounds, as fiberglass laminating resins and in non-metallic auto-body fillers. They are also used as the thermoset polymer matrix in pre-pregs. Fiberglass-reinforced unsaturated polyesters find wide application in bodies of yachts and as body parts of cars.

Depending on the chemical structure, polyester can be a thermoplastic or thermoset. There are also polyester resins cured by hardeners; however, the most common polyesters are thermoplastics.[11] The OH group is reacted with an Isocyanate functional compound in a 2 component system producing coatings which may optionally be pigmented. Polyesters as thermoplastics may change shape after the application of heat. While combustible at high temperatures, polyesters tend to shrink away from flames and self-extinguish upon ignition. Polyester fibers have high tenacity and E-modulus as well as low water absorption and minimal shrinkage in comparison with other industrial fibers.

Increasing the aromatic parts of polyesters increases their glass transition temperature, melting temperature, thermostability, chemical stability, and solvent resistance.

Polyesters can also be telechelic oligomers like the polycaprolactone diol (PCL) and the polyethylene adipate diol (PEA). They are then used as prepolymers.

Aliphatic vs. aromatic polymers

[edit]

Thermally stable polymers, which generally have a high proportion of aromatic structures, are also called high-performance plastics. This application-oriented classification compares such polymers with engineering plastics and commodity plastics. The continuous service temperature of high-performance plastics is generally stated as being higher than 150 °C,[12] whereas engineering plastics (such as polyamide or polycarbonate) are often defined as thermoplastics that retain their properties above 100 °C.[13] Commodity plastics (such as polyethylene or polypropylene) have in this respect even greater limitations, but they are manufactured in great amounts at low cost.

Poly(ester imides) contain an aromatic imide group in the repeat unit, the imide-based polymers have a high proportion of aromatic structures in the main chain and belong to the class of thermally stable polymers. Such polymers contain structures that impart high melting temperatures, resistance to oxidative degradation and stability to radiation and chemical reagents. Among the thermally stable polymers with commercial relevance are polyimides, polysulfones, polyetherketones, and polybenzimidazoles. Of these, polyimides are most widely applied.[14] The polymers’ structures result also in poor processing characteristics, in particular a high melting point and low solubility. The named properties are in particular based on a high percentage of aromatic carbons in the polymer backbone which produces a certain stiffness.[15] Approaches for an improvement of processability include the incorporation of flexible spacers into the backbone, the attachment of stable pendent groups or the incorporation of non-symmetrical structures. Flexible spacers include, for example, ether or hexafluoroisopropylidene, carbonyl or aliphatic groups like isopropylidene; these groups allow bond rotation between aromatic rings. Less symmetrical structures, for example, based on meta– or ortho-linked monomers, introduce structural disorder, decreasing the crystallinity.[4]

The generally poor processability of aromatic polymers (for example, a high melting point and a low solubility) also limits the available options for synthesis and may require strong electron-donating co-solvents like HFIP or TFA for analysis (e. g. 1H NMR spectroscopy) which themselves can introduce further practical limitations.

Uses and applications

[edit]

Fabrics woven or knitted from polyester thread or yarn are used extensively in apparel and home furnishings, from shirts and pants to jackets and hats, bed sheets, blankets, upholstered furniture and computer mouse mats. Industrial polyester fibers, yarns and ropes are used in car tire reinforcements, fabrics for conveyor belts, safety belts, coated fabrics and plastic reinforcements with high-energy absorption. Polyester fiber is used as cushioning and insulating material in pillows, comforters, stuffed animals and characters, and upholstery padding. Polyester fabrics are highly stain-resistant since polyester is a hydrophobic material, making it hard to absorb liquids. The only class of dyes which can be used to alter the color of polyester fabric are what are known as disperse dyes.[16]

Polyesters are also used to make bottles, films, tarpaulin, sails[17] (Dacron), canoes, liquid crystal displays, holograms, filters, dielectric film for capacitors, film insulation for wire and insulating tapes. Polyesters are widely used as a finish on high-quality wood products such as guitars, pianos, and vehicle/yacht interiors. Thixotropic properties of spray-applicable polyesters make them ideal for use on open-grain timbers, as they can quickly fill wood grain, with a high-build film thickness per coat. It can be used for fashionable dresses, but it is most admired for its ability to resist wrinkling and shrinking while washing the product. Its toughness makes it a frequent choice for children’s wear. Polyester is often blended with other fibres like cotton to get the desirable properties of both materials. Cured polyesters can be sanded and polished to a high-gloss, durable finish.

Production

[edit]

Polyester is typically produced through a process known as polymerization. For polyethylene terephthalate (PET), the production process involves the chemical reaction between two primary raw materials: purified terephthalic acid (PTA) or dimethyl terephthalate (DMT) and monoethylene glycol (MEG).

The production process includes the following steps:

- Polycondensation Reaction: The reaction between PTA or DMT and MEG creates polyester polymer chains through a process called polycondensation. This reaction takes place at high temperatures and involves the removal of water or methanol byproducts.

- Extrusion: Once the polymerization is complete, the molten polyester is extruded into long strands. These strands are then cooled and cut into small pellets or chips.

- Spinning: To form fibers, these polyester chips are melted and extruded through spinnerets, forming fine strands of polyester filament. These filaments can be processed further to create continuous fibers, which are then woven into textiles.

- Recycling: The production of polyester has evolved to include the recycling of PET, especially from post-consumer plastic bottles. Recycled PET (rPET) is increasingly being used in textile production, reducing the environmental impact of polyester manufacturing.

Polyethylene terephthalate, the polyester with the greatest market share, is a synthetic polymer made of purified terephthalic acid (PTA) or its dimethyl ester dimethyl terephthalate (DMT) and monoethylene glycol (MEG). With 18% market share of all plastic materials produced, it ranges third after polyethylene (33.5%) and polypropylene (19.5%) and is counted as commodity plastic.

There are several reasons for the importance of polyethylene terephthalate:

- The relatively easy accessible raw materials PTA or DMT and MEG

- The very well understood and described simple chemical process of its synthesis

- The low toxicity level of all raw materials and side products during production and processing

- The possibility to produce PET in a closed loop at low emissions to the environment

- The outstanding mechanical and chemical properties

- The recyclability

- The wide variety of intermediate and final products.

In the following table, the estimated world polyester production is shown. Main applications are textile polyester, bottle polyester resin, film polyester mainly for packaging and specialty polyesters for engineering plastics.

| Product type | 2002 (million tonnes/year) | 2008 (million tonnes/year) |

|---|---|---|

| Textile-PET | 20 | 39 |

| Resin, bottle/A-PET | 9 | 16 |

| Film-PET | 1.2 | 1.5 |

| Special polyester | 1 | 2.5 |

| Total | 31.2 | 59 |

Polyester processing

[edit]

After the first stage of polymer production in the melt phase, the product stream divides into two different application areas which are mainly textile applications and packaging applications. In the following table, the main applications of textile and packaging of polyester are listed.

| Textile | Packaging |

|---|---|

| Staple fiber (PSF) | Bottles for CSD, water, beer, juice, detergents, etc. |

| Filaments POY, DTY, FDY | A-PET film |

| Technical yarn and tire cord | Thermoforming |

| Non-woven and spunbond | biaxial-oriented film (BO-PET) |

| Mono-filament | Strapping |

Abbreviations:PSFPolyester-staple fiberPOYPartially oriented yarnDTYDrawn textured yarnFDYFully drawn yarnCSDCarbonated soft drinkA-PETAmorphous polyethylene terephthalate filmBO-PETBiaxial-oriented polyethylene terephthalate film

A comparable small market segment (much less than 1 million tonnes/year) of polyester is used to produce engineering plastics and masterbatch.

In order to produce the polyester melt with a high efficiency, high-output processing steps like staple fiber (50–300 tonnes/day per spinning line) or POY /FDY (up to 600 tonnes/day split into about 10 spinning machines) are meanwhile more and more vertically integrated direct processes. This means the polymer melt is directly converted into the textile fibers or filaments without the common step of pelletizing. We are talking about full vertical integration when polyester is produced at one site starting from crude oil or distillation products in the chain oil → benzene → PX → PTA → PET melt → fiber/filament or bottle-grade resin. Such integrated processes are meanwhile established in more or less interrupted processes at one production site. Eastman Chemicals were the first to introduce the idea of closing the chain from PX to PET resin with their so-called INTEGREX process. The capacity of such vertically integrated production sites is >1000 tonnes/day and can easily reach 2500 tonnes/day.

Besides the above-mentioned large processing units to produce staple fiber or yarns, there are ten thousands of small and very small processing plants, so that one can estimate that polyester is processed and recycled in more than 10 000 plants around the globe. This is without counting all the companies involved in the supply industry, beginning with engineering and processing machines and ending with special additives, stabilizers and colors. This is a gigantic industry complex and it is still growing by 4–8% per year, depending on the world region.

Synthesis

[edit]

Synthesis of polyesters is generally achieved by a polycondensation reaction. The general equation for the reaction of a diol with a diacid is:(n+1) R(OH)2 + n R'(COOH)2 → HO[ROOCR’COO]nROH + 2n H2O.

Polyesters can be obtained by a wide range of reactions of which the most important are the reaction of acids and alcohols, alcoholysis and or acidolysis of low-molecular weight esters or the alcoholysis of acyl chlorides. The following figure gives an overview over such typical polycondensation reactions for polyester production. Furthermore, polyesters are accessible via ring-opening polymerization.

Azeotrope esterification is a classical method for condensation. The water formed by the reaction of alcohol and a carboxylic acid is continually removed by azeotropic distillation. When melting points of the monomers are sufficiently low, a polyester can be formed via direct esterification while removing the reaction water via vacuum.

Direct bulk polyesterification at high temperatures (150 – 290 °C) is well-suited and used on the industrial scale for the production of aliphatic, unsaturated, and aromatic–aliphatic polyesters. Monomers containing phenolic or tertiary hydroxyl groups exhibit a low reactivity with carboxylic acids and cannot be polymerized via direct acid alcohol-based polyesterification.[4] In the case of PET production, however, the direct process has several advantages, in particular a higher reaction rate, a higher attainable molecular weight, the release of water instead of methanol and lower storage costs of the acid when compared to the ester due to the lower weight.[1]

Alcoholic transesterification

[edit]

Main article: Transesterification

Transesterification: An alcohol-terminated oligomer and an ester-terminated oligomer condense to form an ester linkage, with loss of an alcohol. R and R’ are the two oligomer chains, R” is a sacrificial unit such as a methyl group (methanol is the byproduct of the esterification reaction).

The term “transesterification” is typically used to describe hydroxy–ester, carboxy–ester, and ester–ester exchange reactions. The hydroxy–ester exchange reaction possesses the highest rate of reaction and is used for the production of numerous aromatic–aliphatic and wholly aromatic polyesters.[4] The transesterification based synthesis is particularly useful for when high melting and poorly soluble dicarboxylic acids are used. In addition, alcohols as condensation product are more volatile and thereby easier to remove than water.[18]

The high-temperature melt synthesis between bisphenol diacetates and aromatic dicarboxylic acids or in reverse between bisphenols and aromatic dicarboxylic acid diphenyl esters (carried out at 220 to 320 °C upon the release of acetic acid) is, besides the acyl chloride based synthesis, the preferred route to wholly aromatic polyesters.[4]

Acylation

[edit]

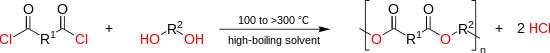

In acylation, the acid begins as an acyl chloride, and thus the polycondensation proceeds with emission of hydrochloric acid (HCl) instead of water.

The reaction between diacyl chlorides and alcohols or phenolic compounds has been widely applied to polyester synthesis and has been subject of numerous reviews and book chapters.[4][19][20][21] The reaction is carried out at lower temperatures than the equilibrium methods; possible types are the high-temperature solution condensation, amine catalysed and interfacial reactions. In addition, the use of activating agents is counted as non-equilibrium method. The equilibrium constants for the acyl chloride-based condensation yielding yielding arylates and polyarylates are very high indeed and are reported to be 4.3 × 103 and 4.7 × 103, respectively. This reaction is thus often referred to as a ‘non-equilibrium’ polyesterification. Even though the acyl chloride based synthesis is also subject of reports in the patent literature, it is unlikely that the reaction is utilized on the production scale.[22] The method is limited by the acid dichlorides’ high cost, its sensitivity to hydrolysis and the occurrence of side reactions.[23]

The high temperature reaction (100 to > 300 °C) of an diacyl chloride with an dialcohol yields the polyester and hydrogen chloride. Under these relatively high temperatures the reaction proceeds rapidly without a catalyst:[21]

The conversion of the reaction can be followed by titration of the evolved hydrogen chloride. A wide variety of solvents has been described including chlorinated benzenes (e.g. dichlorobenzene), chlorinated naphthalenes or diphenyls, as well as non-chlorinated aromatics like terphenyls, benzophenones or dibenzylbenzenes. The reaction was also applied successfully to the preparation of highly crystalline and poorly soluble polymers which require high temperatures to be kept in solution (at least until a sufficiently high molecular weight was achieved).[23]

In an interfacial acyl chloride-based reaction, the alcohol (generally in fact a phenol) is dissolved in the form of an alkoxide in an aqueous sodium hydroxide solution, the acyl chloride in an organic solvent immiscible with water such as dichloromethane, chlorobenzene or hexane, the reaction occurs at the interface under high-speed agitation near room temperature.[21]

The procedure is used for the production of polyarylates (polyesters based on bisphenols), polyamides, polycarbonates, poly(thiocarbonate)s, and others. Since the molecular weight of the product obtained by a high-temperature synthesis can be seriously limited by side reactions, this problem is circumvented by the mild temperatures of interfacial polycondensation. The procedure is applied to the commercial production of bisphenol-A-based polyarylates like Unitika’s U-Polymer.[4] Water could be in some cases replaced by an immiscible organic solvent (e. g. in the adiponitrile/carbon tetrachloride system).[21] The procedure is of little use in the production of polyesters based on aliphatic diols which have higher pKa values than phenols and therefore do not form alcoholate ions in aqueous solutions.[4] The base catalysed reaction of an acyl chloride with an alcohol may also be carried out in one phase using tertiary amines (e. g. triethylamine, Et3N) or pyridine as acid acceptors:

While acyl chloride-based polyesterifications proceed only very slowly at room temperature without a catalyst, the amine accelerates the reaction in several possible ways, although the mechanism is not fully understood.[21] However, it is known that tertiary amines can cause side-reactions such as the formation of ketenes and ketene dimers.[24]

Silyl method

[edit]

In this variant of the HCl method, the carboxylic acid chloride is converted with the trimethyl silyl ether of the alcohol component and production of trimethyl silyl chloride is obtained

Acetate method (esterification)

[edit]

Ring-opening polymerization

[edit]

Aliphatic polyesters can be assembled from lactones under very mild conditions, catalyzed anionically, cationically, metallorganically or enzyme-based.[25][26] A number of catalytic methods for the copolymerization of epoxides with cyclic anhydrides have also recently been shown to provide a wide array of functionalized polyesters, both saturated and unsaturated. Ring-opening polymerization of lactones and lactides is also applied on the industrial scale.[27][28]

Other methods

[edit]

Numerous other reactions have been reported for the synthesis of selected polyesters, but are limited to laboratory-scale syntheses using specific conditions, for example using dicarboxylic acid salts and dialkyl halides or reactions between bisketenes and diols.[4]

Instead of acyl chlorides, so-called activating agents can be used, such as 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole, dicyclohexylcarbodiimide, or trifluoroacetic anhydride. The polycondensation proceeds via the in situ conversion of the carboxylic acid into a more reactive intermediate while the activating agents are consumed. The reaction proceeds, for example, via an intermediate N-acylimidazole which reacts with catalytically acting sodium alkoxide:[4]

The use of activating agents for the production of high-melting aromatic polyesters and polyamides under mild conditions has been subject of intensive academic research since the 1980s, but the reactions have not gained commercial acceptance as similar results can be achieved with cheaper reactants.[4]

Thermodynamics of polycondensation reactions

[edit]

Polyesterifications are grouped by some authors[4][19] into two main categories: a) equilibrium polyesterifications (mainly alcohol-acid reaction, alcohol–ester and acid–ester interchange reactions, carried out in bulk at high temperatures), and b) non-equilibrium polyesterifications, using highly reactive monomers (for example acid chlorides or activated carboxylic acids, mostly carried out at lower temperatures in solution).

The acid-alcohol based polyesterification is one example of an equilibrium reaction. The ratio between the polymer-forming ester group (-C(O)O-) and the condensation product water (H2O) against the acid-based (-C(O)OH) and alcohol-based (-OH) monomers is described by the equilibrium constant KC.KC=[…−C(O)O−…][H2O][−C(O)OH][−OH]

![{\displaystyle K_{C}={\frac {[...{\ce {-C(O)O -}}...][{\ce {H2O}}]}{[{\ce {-C(O)OH}}][{\ce {-OH}}]}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/950760988a3cc1808cfa80ab840d5e3d13654d59)

The equilibrium constant of the acid-alcohol based polyesterification is typically KC ≤ 10, what is not high enough to obtain high-molecular weight polymers (DPn ≥ 100), as the number average degree of polymerization (DPn) can be calculated from the equilibrium constant KC.[20]DPn = KC2+1

![{\displaystyle DP_{n}~=~{\sqrt[{2}]{K_{C}}}+1}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5299262cb76bec69c3a62c8dab17c3cc904da956)

In equilibrium reactions, it is therefore necessary to remove the condensation product continuously and efficiently from the reaction medium in order to drive the equilibrium towards polymer.[20] The condensation product is therefore removed at reduced pressure and high temperatures (150–320 °C, depending on the monomers) to prevent the back reaction.[8] With the progress of the reaction, the concentration of active chain ends is decreasing and the viscosity of the melt or solution increasing. For an increase of the reaction rate, the reaction is carried out at high end group concentration (preferably in the bulk), promoted by the elevated temperatures.

Equilibrium constants of magnitude KC ≥ 104 are achieved when using reactive reactants (acid chlorides or acid anhydrides) or activating agents like 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole. Using these reactants, molecular weights required for technical applications can be achieved even without active removal of the condensation product.

History

[edit]

In 1926, United States–based DuPont began research on large molecules and synthetic fibers. This early research, headed by Wallace Carothers, centered on what became nylon, which was one of the first synthetic fibers.[29] Carothers was working for DuPont at the time. Carothers’ research was incomplete and had not advanced to investigating the polyester formed from mixing ethylene glycol and terephthalic acid. In 1928 polyester was patented in Britain by the British General Electric Company.[30] Carothers’ project was revived by British scientists Whinfield and Dickson, who patented polyethylene terephthalate (PET) or PETE in 1941. Polyethylene terephthalate forms the basis for synthetic fibers like Dacron, Terylene and polyester. In 1946, DuPont bought all legal rights from Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI).[1]

Biodegradation and environmental concerns

[edit]

Main article: Biodegradation

The Futuro houses were made of fibreglass-reinforced polyester plastic; polyester-polyurethane, and poly(methyl methacrylate). One house was found to be degrading by cyanobacteria and Archaea.[31][32]

Cross-linking

[edit]

Unsaturated polyesters are thermosetting polymers. They are generally copolymers prepared by polymerizing one or more diols with saturated and unsaturated dicarboxylic acids (maleic acid, fumaric acid, etc.) or their anhydrides. The double bond of unsaturated polyesters reacts with a vinyl monomer, usually styrene, resulting in a 3-D cross-linked structure. This structure acts as a thermoset. The exothermic cross-linking reaction is initiated through a catalyst, usually an organic peroxide such as methyl ethyl ketone peroxide or benzoyl peroxide.

Pollution of freshwater and seawater habitats

[edit]

A team at Plymouth University in the UK spent 12 months analysing what happened when a number of synthetic materials were washed at different temperatures in domestic washing machines, using different combinations of detergents, to quantify the microfibres shed. They found that an average washing load of 6 kg could release an estimated 137,951 fibres from polyester-cotton blend fabric, 496,030 fibres from polyester and 728,789 from acrylic. Those fibers add to the general microplastics pollution.[33][34][35]

Safety

[edit]

Fertility

[edit]

Ahmed Shafik was a sexologist who won a Ig Nobel Prize on his research regarding how polyester can affect the fertility of rats,[36] dogs,[37] and men.[38]

Bisphenol A which is a endocrine disrupting chemical may be used in the synthesis of polyester.[39]

Recycling

[edit]

Recycling of polymers has become very important as the production and use of plastic is continuously rising. Global plastic waste may almost triple by 2060 if this continues.[40] Plastics can be recycled by various means like mechanical recycling, chemical recycling, etc. Among the recyclable polymers, polyester PET is one of the most recycled plastics.[41][42] The ester bond present in polyesters is susceptible to hydrolysis (acidic or basic conditions), methanolysis and glycolysis which makes this class of polymers suitable for chemical recycling.[43] Enzymatic/biological recycling of PET can be carried out using different enzymes like PETase, cutinase, esterase, lipase, etc.[44] PETase has been also reported for enzymatic degradation of other synthetic polyesters (PBT, PHT, Akestra™, etc.) which contains similar aromatic ester bond as that of PET.[45]